There is at the heart of Christianity something of split – a dichotomy, if you’d prefer between the opposing forces of individualism and community. These two tendencies which pull in opposite directions are also strongly and markedly at work in the rest of the world, not just here in the Church. We see from very early days the desire to withdraw and be alone in prayer and contemplation with God. Some of the early desert fathers were doing precisely this and so were the anchorites. And there were even more extreme versions of this. While I have never felt remotely drawn to the solitary life, I can say with complete conviction that I have always had an active aversion to the idea of living on top of a pillar as a stylite – a popular form of asceticism in the eastern church – where perhaps the weather is a little kinder for one thing. So, at one end of the spectrum we find the solitaries and at the other there are the communities where people choose consciously to live together – often with a shared set of values or a Rule. In my present post I am blessed to be living in a part of the medieval infirmary of a Benedictine community in Peterborough in what used to be the monastery.

And it seems to me that the pull of individualism is very strong at the moment in our world, there are all manner of competing ideologies proclaiming ‘me, me, me’ at the top of their voices. We hear the language of rights rather than responsibilities which suggests a strong emphasis on the individual rather than the communal. And yet the other end of the spectrum should not be forgotten. John Donne famously said in his devotions of 1624 ‘No man is an Island, entire of it self; every man is a piece of the Continent, a part of the main.” In other words we are all joined together in some way – and had he lived in a later age, I am sure he would have said ‘no-one is an island’ because he would have included women as well as men. At the beginning of Genesis we read God’s comment that ‘it is not good for the man to be alone.’ Again we see that together is being stressed in opposition to being alone. Taken at its broadest sweep, much of the OT is the story of the people of Israel as a community. The Pentateuch is a collection of laws to show the people of Israel how to live as a community.

And the tendency to draw together rather than draw apart also has a very long and distinguished Christian history . Some of the early fathers were drawn into community just as some of them were solitary. St Anthony of Egypt is perhaps the most famous, though certainly not the first. And over time his example spread throughout Christendom. I have already mentioned Peterborough Abbey which was followed the rule of St Benedict, known as the founder of western monasticism. His influence is still alive and well in the world today. There is even a ‘new monasticism’ movement – but that seems to mean different things to different people.

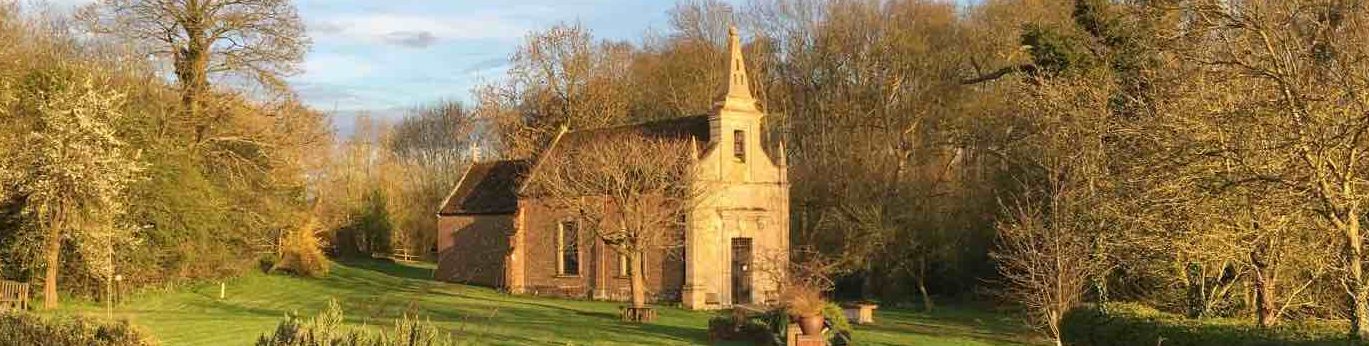

Many of you here will know the history of this community in Little Gidding far better than I – and all of us will have learnt something from Bridget’s sermon this morning at the start of our day. Little Gidding is only one of very many communities – even if it is the one which is dearest to us here.

But in our modern technological world, we have seen the rise of new, virtual communities which do not exist in the same way as their predecessors did. In the age of the internet, you don’t need to be physically next to or near someone in order to share their beliefs or world view – as long as you have a computer and access to the world wide web you can be a member of a community which exists everywhere and nowhere. It is surely no coincidence that these virtual communities have come into existence in our increasingly self-centred and individualistic world. Almost as if there are a bit of a contradiction in terms. By definition, a community is a collection of individuals, but these virtual communities take this inherent tension to a whole new level. They are made of up of angry or lonely individuals who may never meet each other, but still feel that sense of belonging and identity which is what community bestows. The new online communities are a challenge to our definition of what a community actually is –because they are most certainly not communities in the way that this place was once of collection of people who lived and worked and worshipped together.

In our increasingly fragmented world, it seems to me that one of the greatest gifts that the church can offer our broken and divided is the gift and opportunity of coming together as community. We believe in community because ultimately our God is a living demonstration of a perfect community. The holy Trinity is, of course, a mystery beyond our poor human understanding, but whatever else we can say about the Trinity, it certainly shows how the One God whom we worship values community. We can say this because the of Three Persons of Father, Son and Holy Spirit who live together in the perfect community of love.

So what has all this got to do with us? Is it just a case of a gentle stroll in some spectacularly beautiful countryside with a bit of religion thrown in? I think what we might take from today is the idea that coming together is not only an enjoyable pastime but it is also a theological statement. Together we are the body of Christ, not individually and together we are able to demonstrate something of God’s love and plan for the world. So go back to your churches and bring others with you that they may know and experience the joy of community – yes and sometimes the difficulties as well – let’s be realistic! But being together is what Jesus called us to do so that together we can go out and make disciples of all nations and teach them to observe all that Jesus commands us.

Dr Bridget Nichols’ and Canon Tim Alban Jones’s addresses at the five stations

Dr Bridget Nichols’ sermon at the morning Eucharist at Leighton Bromswold