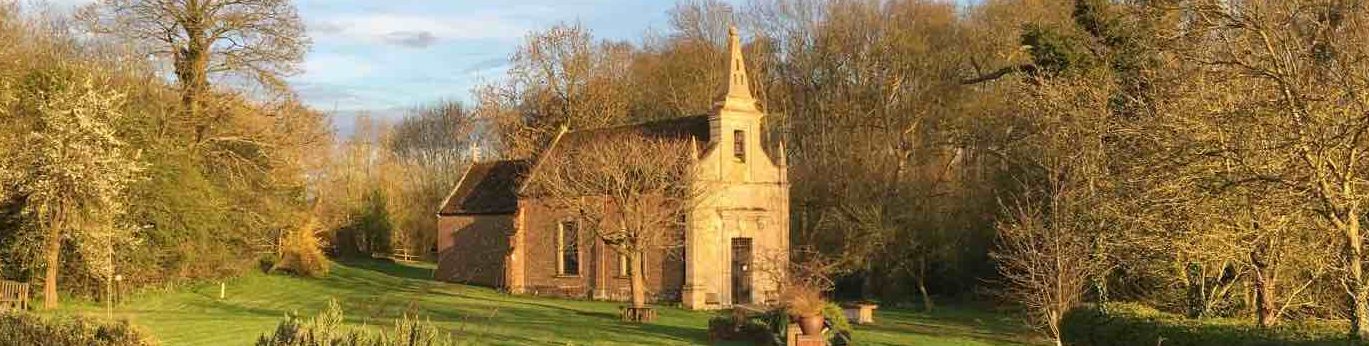

First Station (Hundred Stone, Leighton Bromswold)

Psalm 21. Domine, in virtute tua

1. The King shall rejoice in thy strength, O Lord : exceeding glad shall he be of thy salvation.

2. Thou hast given him his heart’s desire : and hast not denied him the request of his lips.

3. For thou shalt prevent him with the blessings of goodness : and shalt set a crown of pure gold upon his head.

4. He asked life of thee, and thou gavest him a long life : even for ever and ever.

5. His honour is great in thy salvation : glory and great worship shalt thou lay upon him.

6. For thou shalt give him everlasting felicity : and make him glad with the joy of thy countenance.

7. And why? because the King putteth his trust in the Lord : and in the mercy of the most Highest he shall not miscarry.

8. All thine enemies shall feel thine hand : thy right hand shall find out them that hate thee.

9. Thou shalt make them like a fiery oven in time of thy wrath : the Lord shall destroy them in his displeasure, and the fire shall consume them.

10. Their fruit shalt thou root out of the earth : and their seed from among the children of men.

11. For they intended mischief against thee : and imagined such a device as they are not able to perform.

12. Therefore shalt thou put them to flight : and the strings of thy bow shalt thou make ready against the face of them.

13. Be thou exalted, Lord, in thine own strength : so we will sing, and praise thy power.

Royal Psalms

One of the themes that runs through the book of psalms is that of kingship. There are a number of so called ‘royal psalms’. We should not be surprised at this. Even to this day one of the best way of selling newspapers is by putting a royal story on the front cover. And if you can twist the story to include – however tangentally – a picture of the late princess of Wales, well, it’s a sell-out! And if you doubt me, just look at the coverage of the announcement by the Duke of Edinburgh last week. The royal psalms are obviously not in the same sensationalist game as the worst of the red-topped tabloids, but they do seem to show an abiding interest in all matters to do with the royal family of the day and those in authority.

The dating of the psalms is notoriously difficult. There are very few direct historical references. One of the great watershed moments in the history of Israel was the exile; it is one of the defining events in Jewish history. The king of Babylon besieged Jerusalem and when the city fell, he sent the leading citizens into exile where they remained for about 70 years. The exact dates are not important here, but the importance of the event to the national psyche and sense of identity can hardly be overstated. And this national calamity helps us date the so called royal psalms because they pre-suppose the existence of a King and therefore must have been written before the exile.

The people of Israel did without Kings for a long time. The first king was Saul, a flawed character, who reigned from about 1050 – 1012BC. He was succeeded not by his son, but by his son-in-law, King David, whose connection with the psalms is very well known. In the BCP, the whole psalter is referred to as ‘The Psalms of David’ even though we all know that he didn’t write all of them. Some of them pre-date the great King, and many of them date from after his death. But the psalter has a very distinctive strand of ‘bigging up’ the Kings. Ps 21 is only one example of many from which I could have chosen. Others were also chosen by Handel when setting the coronation anthems: My heart is inditing and Let thy hand be strengthened contain verses from psalms 45 and 89 and are in a similar vein. I will admit that as I was preparing this little talk, I found myself humming the themes from these Handel anthems so much, that I had to go and find the CD of them and play them.

So what do the royal psalms have to tell us today in 2017? What’s in them for us? I think they provide us a very timely opportunity to reflect on the nature of not only of kingship and monarchy (be that constitutional and 21st century or Biblical and Davidian) but also about the nature of power and authority. I say timely, of course, because of the forthcoming General Election. The royal psalms show us that true and authentic authority has its origins not in human power, but because all power ultimately comes through and from God. In Psalm 21 we see this in the clearest possible terms. We read that the king has all sorts of great blessings; he has received his heart’s desire, he has been given a long life and everlasting felicity. “And why? because the King putteth this trust in the Lord: and in the mercy of the Most Highest he shall not miscarry.” A more modern translation renders that verse: “the king puts his trust in the Lord; the loving care of the Most High keeps him unshaken.” It would be easy to use – perhaps twist – this idea to promote the idea of the divine right of kings, but that’s not what I am about today. I would like you to consider as you walk, the nature of power and those who exercise it.

We can all think of examples where power and authority have led to great evils and untold misery. And those examples are not confined the pages of history; Hitler and Stalin have their modern day counterparts ; think of President Mugabe or the terrifying situation in North Korea where power is unchecked in the hands of an evidently dangerous and unstable man. But many if not all of us find ourselves in positions of power from time to time – at work, or at home. Perhaps, as you walk, you could think, also, of how you use power.

Tim Alban Jones

Crown us, O God, with humility,

and robe us with compassion,

that, as you call us in to the kingdom of your Son,

we may strive to overcome all evil by the power of good

and so walk gently on the earth with you, our God, for ever.

Second Station (Salome Wood)

Psalm 126. In convertendo

1. When the Lord turned again the captivity of Sion : then were we like unto them that dream.

2. Then was our mouth filled with laughter : and our tongue with joy.

3. Then said they among the heathen : The Lord hath done great things for them.

4. Yea, the Lord hath done great things for us already : whereof we rejoice.

5. Turn our captivity, O Lord : as the rivers in the south.

6. They that sow in tears : shall reap in joy.

7. He that now goeth on his way weeping, and beareth forth good seed : shall doubtless come again with joy, and bring his sheaves with him.

A Song of Ascents

This psalm belongs to a set of psalms (120-134), each bearing the title ‘A Song of Ascents’. They are thought to have been sung by pilgrims going up to Jerusalem, and their subject matter covers both material and spiritual protection. Pilgrims over the ages have been vulnerable to attack on the road, which is a good reason for travelling in a large company. Pilgrimage also creates other vulnerabilities – they are times when we deliberately put ourselves in the position of seekers after God and they can be daunting: daunting when God finds us; daunting when we find ourselves. Many of these psalms trace a path from misery to joy and when they don’t, they depend nevertheless on the constant presence of God who defends us in the darkest places.

Psalm 126 manages to acknowledge, embrace and transform misery in a shout of joy. Here, the pilgrims remember as they go up to Jerusalem what it was like for their ancestors to see God’s holy city ruined and some of their neighbours taken into exile. The general view of current scholars is that the Babylonians didn’t march the whole population into captivity. It was people of higher status and greater prominence in public office who interested them. Nor did these people necessarily have a terrible time in exile. But as we know from Psalm 137, they hated being far from the place that represented the presence of God among them, at last permanently at home among his people. They could not sing the Lord’s song in a strange land.

The pilgrims who sang Psalm 126 didn’t only remember that. They remembered also what it was like to come back. We have all known at one time or another what it is like to encounter the kind of happiness we hardly dare to believe in. It is like a waking dream. Perhaps we even do uncharacteristically extrovert things, like bursting into song in public.

How did this become a prayer for later pilgrims? What did the Ferrars remember as they prayed it? The failure of the Virginia Company venture? The end of a life in London? The longing for a new place and a new way of life?

How does this psalm become a prayer that we can adopt? Dry riverbeds have a real and potent meaning in the water-starved conditions of the Middle East. They have also been used as a metaphor for desolation, the apparent drying up of material security, or creative energy, or spiritual liveliness. One rainfall can change everything. The metaphor extends. Seeds sown in the hopelessness of drought spring up when the new water supply arrives. So this is a song of hope and trust in the God who does not desert us, whatever the outward signs might suggest.

Bridget Nichols

Lord, as you send rain and flowers even to the wilderness,

renew us by your Holy Spirit,

help us to sow good seed in time of adversity

and to live to rejoice in your good harvest of all creation;

through Jesus Christ our Lord.

(Common Worship Daily Prayer: Psalm 126)

A prayer from a 7th-century Spanish collection of psalm collects

Deal generously with us, O Lord,

and console us with the return of true joy,

and though we have laboured through these times in tears,

may we gather the fruits of eternity when the harvest comes,

that what we have sown with so many tears

may be rewarded with joy and blessing.

Third Station (Hamerton)

Psalm 79. Deus, venerunt

1. O God, the heathen are come into thine inheritance : thy holy temple have they defiled, and made Jerusalem an heap of stones.

2. The dead bodies of thy servants have they given to be meat unto the fowls of the air : and the flesh of thy saints unto the beasts of the land.

3. Their blood have they shed like water on every side of Jerusalem : and there was no man to bury them.

4. We are become an open shame to our enemies : a very scorn and derision unto them that are round about us.

5. Lord, how long wilt thou be angry : shall thy jealousy burn like fire for ever?

6. Pour out thine indignation upon the heathen that have not known thee : and upon the kingdoms that have not called upon thy Name.

7. For they have devoured Jacob : and laid waste his dwelling-place.

8. O remember not our old sins, but have mercy upon us, and that soon : for we are come to great misery.

9. Help us, O God of our salvation, for the glory of thy Name : O deliver us, and be merciful unto our sins, for thy Name’s sake.

10. Wherefore do the heathen say : Where is now their God?

11. O let the vengeance of thy servants’ blood that is shed : be openly shewed upon the heathen in our sight.

12. O let the sorrowful sighing of the prisoners come before thee : according to the greatness of thy power, preserve thou those that are appointed to die.

13. And for the blasphemy wherewith our neighbours have blasphemed thee : reward thou them , O Lord, seven-fold into their bosom.

14. So we, that are thy people, and sheep of thy pasture, shall give thee thanks for ever : and will alway be shewing forth thy praise from generation to generation.

Lament

One of the things that makes the psalms so relevant for all time and all occasions is that they speak of and they speak to just about every possible human emotion. There are psalms for when you’re feeling exhilarated with joy and when you are in the depths of despair; there are psalms for praising the glory of God – through the wonders of creation in the earth, or through the worship of the temple or through his wisdom displayed in the law. There are also psalms for when things are not going so well; for when you want to curse your enemies and those which express an almost blood-curdling thirst for revenge and many other distinctly less-than-Christian emotions. One of the major themes of the psalms is that of lament. And these psalms of lament can be further divided into individual or corporate lament. Sometimes it’s the psalmist alone who sings the blues, and sometimes it’s the whole community which is corporately down in the dumps.

The psalm that I have chosen to illustrate this theme of lament is a corporate expression of grief and sorrow over the destruction of the temple. I could just as easily have chosen a number of other psalms and indeed 74 is very similar in mood and theme. I chose 79 rather than 74 for the simple reason that it is shorter. I mentioned the important event of the exile in my first talk and one of the most significant parts of the whole time was the way in which the Babylonians destroyed the temple in Jerusalem, which had become the focus of worship. It had been built by the great King Solomon and had been elevated in importance and status as the centuries passed. In the earliest days of the people of Israel, when they first settled in the promised land, they worshipped in many different places and we see how there was what could be called a centralising tendency to elevate the importance of the temple in Jerusalem as the focus of national worship. The local shrines were suppressed and by the time of the exile, it was all happening in Jerusalem; which makes the destruction of the temple all the more heart-rending and difficult for the people of Israel.

I said earlier that it was difficult to date the psalms, but this one here contains a direct reference to the destruction of the temple. Scholars tell us that this refers to the destruction of Solomon’s temple (the so called first temple) by the Babylonians following the calamitous 18 month siege of Jerusalem. Some commentators suggest that what is being referred to is a profanation of the temple rather the its destruction – and in the course of the history of Israel both those events took place. Whichever event is being referred to here – and I think it reads more about destruction than despoiling – it s certainly a cause for a corporate lament.

It is worthy of note that there are a couple of verses which are almost identical to some verses from the book of Jeremiah and Lamentations. Jeremiah 10.25 is identical to verse 6 of the psalm. Certainly one is quoting the other, though it is not possible to say for certain whether Jeremiah is quoting the psalm, or the psalmist is quoting the prophet.

I mentioned earlier that there were some pretty un-Christian sentiments in the psalms – one of the things that make this a very human collection. We certainly see some of that here in this psalm. In verses 6, 11 and 13 we see a cry for vengeance. After starting out with a description of the sorry state of affairs, the psalmist ascribes the cause of it as God’s anger and jealousy (verse 5). And the psalm ends with what sounds like a rather incongruous verse of praise. After God has repaid the enemy seven-fold into their bosom, then the people of Israel will be able to thank him and praise him from one generation to another.

But this emotion of lamenting is the one I would like us to think about for a few moments. It seems just as current and up to date as it was hundreds of years ago. There are situations in the world today that are just as tragic and lamentable – in the true sense of that word. We hear of young people contracting cancer, or someone being knocked over crossing a road and suffering life-changing injuries; and we hear of wars and almost indescribable violence and suffering; we see pictures of refugees clinging to make-shift boats risking their lives in search of a better way of life and in Peterborough where I live, I daily see people sleeping in shop doorways and begging for food. The sheer injustice and the scale of it all is enough to make one weep -and that is exactly what these psalms of lament are about. When confronted with something that is too big and too terrible, lamentation is an entirely appropriate response. It’s not the same as moaning or whinging. It’s about offering to God our own inadequacies and inability to do anything about the unfairness of our human lot.

The sacking of Little Gidding by the Puritans after the death of Nicholas Ferrar was the cause of much lamenting. All the good that had been built up was laid waste. As we walk on to our next stop, perhaps you might like to think about some of the things or situations which cause us to lament today; in our church, in our world, in our lives or in our society.

Tim Alban Jones

When faith is scorned

and love grows cold,

then, God of hosts, rebuild your Church

on lives of thankfulness and prayer;

through Christ your eternal Son.

Fourth Station (Steeple Gidding)

Psalm 112. Beatus vir

1. Blessed is the man that feareth the Lord : he hath great delight in his commandments.

2. His seed shall be mighty upon earth : the generation of the faithful shall be blessed.

3. Riches and plenteousness shall be in his house : and his righteousness endureth for ever.

4. Unto the godly there ariseth up light in the darkness : he is merciful, loving, and righteous.

5. A good man is merciful, and lendeth : and will guide his words with discretion.

6. For he shall never be moved : and the righteous shall be had in everlasting remembrance.

7. He will not be afraid of any evil tidings : for his heart standeth fast, and believeth in the Lord.

8. His heart is established, and will not shrink : until he see his desire upon his enemies.

9. He hath dispersed abroad, and given to the poor : and his righteousness remaineth for ever; his horn shall be exalted with honour.

10. The ungodly shall see it, and it shall grieve him : he shall gnash with his teeth, and consume away; the desire of the ungodly shall perish.

A Wisdom Psalm

The psalms described as Wisdom psalms are not a group, like the Songs of Ascent. Nor do they deal with wisdom in the sense we might expect – a sort of intellectual attainment of a profound nature. It might even be truer to say that in this tradition, wisdom has more to do with character, with a way of life that models itself on God and studies the Law of Moses to find that model. Psalm 119, which could have kept us busy all the way from Leighton Bromswold to Little Gidding, is an extended meditation on the Law. Psalm 112 shares some of its themes, but with more economy.

It makes the traditional connection between wisdom and the fear of the Lord. The fear of God is something discussed most in relation to more sensational forms of discipline. But that is not exactly what the compilers of the psalms and proverbs had in mind. It might be taken rather as a kind of awe and reverence in the presence of holiness. Being wise means, to begin with, being very aware of the unfathomable magnitude of God, and properly respectful of that when trying to approach God. It has something to do with recognising holy ground – the kind of recognition that made Moses take his sandals off at the burning bush.

The characteristics that the psalmist suggests we should learn are attributes of God himself – graciousness and mercy. This is how God describes himself to Moses a little later in the story of the Exodus, as the time comes to give them a law to live by. He does not wish to terrorise his people, but to show them how to live in the closest proximity to him. If they will learn those lessons, then they will find no darkness that cannot be illuminated by God’s presence. And if we are to follow the translation in the NRSV, they too can be lights to others: ‘They rise in the darkness as a light for the upright’.

There are other things too: generosity to the poor; steadiness in the face of trouble; constant trust in God. We are probably more reticent about expecting the sort of visible divine favour that exasperates our unrighteous enemies and causes them to gnash their teeth. I wonder whether this is not least because we have a different understanding of what happens to us after death. If Sheol is a place where you cannot praise God, then of course, it is essential to get things right on earth. If you set your horizon as the resurrection, you will know that Christ has won the most convincing victory over all our enemies. That gives us hope that the opportunity to grow closer to God, and more like God in character will be even greater after death.

The Church remembers Nicholas Ferrar and the community he founded as a particular embodiment of this kind of godly wisdom. They kept company with the most cultivated minds in the district and one of their neighbours was the famous collector of manuscripts, Robert Cotton. But they also lived this example of graciousness and mercy. Simon Kershaw’s proper preface for Ferrar’s commemoration is a portrait of godly wisdom:

We praise you now and give you thanks

for your servant Nicholas Ferrar,

who turned his back on wealth and honours

and with love for you, sought only Christ.

Waiting on his Master by day and by night,

in prayer, study and devotion,

he was drawn closer to you

and witnessed to your greatness and your mercy.

Watching for the day when your promise will be fulfilled,

he glimpsed the glorious splendour of your majesty

in the heavenly banquet of your household.

Bridget Nichols

Generous God,

save us from the meanness

that calculates its interest and hoards its earthly gain;

as we have freely received,

so may we freely give;

in the grace of Jesus Christ our Lord.

(Common Worship Daily Prayer : Psalm 112)

Fifth Station (At the Tomb of Nicholas Ferrar)

Psalm 149. Cantate Domino

1. O sing unto the Lord a new song : let the congregation of saints praise him.

2. Let Israel rejoice in him that made him : and let the children of Sion be joyful in their King.

3. Let them praise his Name in the dance : let them sing praises unto him with tabret and harp.

4. For the Lord hath pleasure in his people : and helpeth the meek-hearted.

5. Let the saints be joyful with glory : let them rejoice in their beds.

6. Let the praises of God be in their mouth : and a two-edged sword in their hands;

7. To be avenged of the heathen : and to rebuke the people;

8. To bind their kings in chains : and their nobles with links of iron.

9. That they may be avenged of them, as it is written : Such honour have all his saints.

Praise

As we know, it is perhaps a little misleading to refer to the book of psalms as if it were written by a single author at a single time. Rather like the whole Bible, the Psalter is a collection of separate items gathered together into a single cover. Originally, of course, even that wouldn’t have been true, because the Hebrew writings were on scrolls not in books. But you get the point. With the so – called Psalms of praise – or what some writers call, Hymnic psalms – we see very clear evidence of the differences in time of writing. A large number of the psalms are of this type – praising God for his greatness, his goodness, his strength, his protection and his other many attributes and qualities. The one I have chosen is one of the last half dozen in our psalter which all fall into this category. They are all dated from after the exile, which makes them perhaps younger than many of the others. It is appropriate then, to sing to the Lord a ‘new song’ for this was intended for the new temple in Jerusalem – the second Temple. In fact there are four psalms which begin with this same opening line: ‘ O sing unto the the Lord a new song.’ We might digress here into the relative values of old or new music in the worship of our contemporary church. If we were to do so, these psalms would suggest that while the notes and music of the songs may be new, the debate is certainly as old as the psalter – and probably older. In the psalms it is clearly expected that God can and should be praised in new songs as well as in the ones that everyone knows. I said we might digress here, but I think we should resist the temptation.

The impulse to praise our God is surely one of the things that sets us apart from the rest of creation. As humans we capable of an awareness of the ‘otherness’ of God – sometimes people use complicated words like transcendence or numinous to express this sense. Even though many people are oblivious to God it in our fast-paced and mad, modern world we all have the capacity to worship and praise is at the very heart of what it means to come to worship. This deep-seated and inbuilt desire to offer praise to a divine being is not a uniquely Christian thing by any means, but it is uniquely human. All the business of sacrificing animals or incense or anything else is a recognition that we are small and insignificant when we are in the presence of God. When we use the phrase ‘sacrifice of praise’ in one of the Eucharistic prayers, it seems to be to be a nod in this direction. When I think about God I am, to quote the prayer book phraseology, ‘a worm and no man’ and when I want to express this or respond, then I find myself praising God. This is exactly the sort of thing going on here. “Let Israel rejoice in him that made him” “Let them praise his Name in the dance; let them sing praises unto him with tabret and harp”. As I managed to resist the pull of a digression on to the merits or otherwise of modern church music, I will also resist the temptation to talk about liturgical dance. But I will just point out, that this is what the people of Israel are being invited to do here.

One of the many problems of our modern world is perhaps that people are offering praise and worship to the wrong things; the false gods of consumerism and greed; the incessant need to have and possess things and stuff. In the presence of God, all that we have is worthless and tawdry. There are a couple of alternative prayers used at the preparation of the table during the communion service which talk along these lines. We ask God to pour upon the poverty of our love and the weakness of our praise the transforming fire of his praise. Or again the marvellous idea that God might make the frailty of our praise a dwelling place for his glory. One important aspect of praising God is that of thanksgiving that he deigns to even notice us, never mind all the many blessings he bestows on us. We need God so much more than he needs us – even though so many people in the world either don’t know this or don’t believe it. When we recognise our dependency on God we cannot fail to praise him. As the psalmist says, “the fear of God is the beginning of wisdom”. The word fear is much less about being terrified and much more about respecting and praising. Praise is a recognition that we are the creatures in the presence of our Creator and that is how it should be.

Tim Alban Jones

Glorious and redeeming God,

give us hearts to praise you all our days

and wills to reject the world’s deceits,

that we may bind the evils of our age

and proclaim the good news of salvation

in Jesus Christ our Lord.

Dr Bridget Nichols’s sermon at the morning Eucharist at Leighton Bromswold

Canon Tim Alban Jones’s sermon at Evensong at Little Gidding