There is a narrow passage in Cambridge, running between Gonville and Caius and Trinity Colleges. It is called Garrett Hostel Lane, and someone, perhaps one of the enterprising young men who lure tourists into very expensive punts, regularly refreshes a chalk inscription on the wall. This reads: ‘To the river.’ Anyone who has read The Wind in the Willows will find that ordinary information full of potential for adventure.

There is a narrow passage in Cambridge, running between Gonville and Caius and Trinity Colleges. It is called Garrett Hostel Lane, and someone, perhaps one of the enterprising young men who lure tourists into very expensive punts, regularly refreshes a chalk inscription on the wall. This reads: ‘To the river.’ Anyone who has read The Wind in the Willows will find that ordinary information full of potential for adventure. But the lane itself, despite its strange cocktail of laundry and kitchen smells, also has a feeling of adventure. It has been there for a very long time, and I have treasured a fantasy of meeting Cranmer there one day, wrapped in his cloak against the East Anglian wind as he returns to Jesus College after a visit to the White Horse Tavern on King’s Parade. Since reading more about Nicholas Ferrar in preparation for today’s pilgrimage, the possibilities have expanded. Now I imagine him too, more of an age with the young men running the punts, taking that route from Clare Hall to get to Trinity Street.

The eight years that Ferrar spent in Cambridge must have done a good deal to shape his idea of community. Arriving as a 13-year old, he would, Alan Maycock tells us in his biography, have been assigned with several other boys to a tutor. The tutor may not have been much older than his charges, and he had a large task. Not only did he teach the boys in his rooms; that was also where they lived. At night, the classroom became a sort of dormitory. By day, the boys pushed their beds under the tutor’s bed and got on with their studies.

For Nicholas, the destination at the end of this was to be employment in the Virginia Company, in which his father had interest. In between, he travelled and studied in Europe, attached to the court of James I’s daughter Elizabeth, who had married the Elector Palatine. He returned to England in I618, but didn’t have many years to become entrenched in colonial trade and commerce. The Virginia Company closed in 1624, with substantial losses to the Ferrar family.

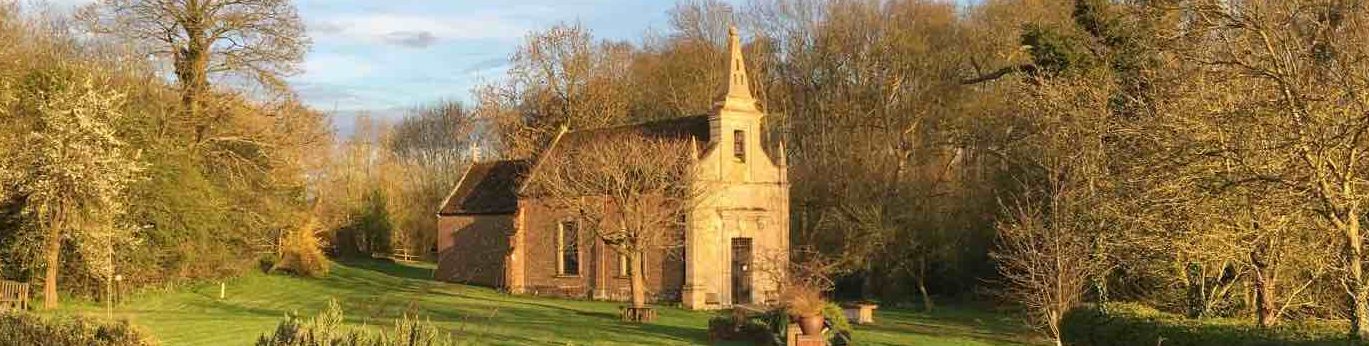

Was it circumstances, coincidence, or a more powerful call from God that moved Nicholas to leave the receipt of custom (Matthew 9.9)? At any rate, he and the family set out to find what Maycock calls ‘a life of retirement from the world and complete self-dedication to God’ (Nicholas Ferrar of Little Gidding, SPCK: 1938, p. 109). He found the ideal place at Little Gidding.

Retirement did not mean idleness, however. The house and church desperately needed restoration and the whole family became involved, even down to creating the textiles to adorn the church. Over three or four years, things were put to rights. In some respects, it sounds like a 17th-century precursor of William Morris’s Arts and Crafts experiment in community life. It is the kind of life that only really works by discipline and structure under a governing vision. Human beings are not always easy to confine peacefully in one place. So what sort of vision was it? Morris, despite his interest in mystery and the legends of antiquity, would certainly not have called it a spirituality. Neither would Ferrar.

Maycock, in his later Chronicles of Little Gidding (SPCK: 1954) is fascinating on this subject. Life at Little Gidding was regulated by the Daily Offices, a monthly celebration of Holy Communion, and disciplined recitation of the Psalms. The Ferrars were Prayer Book people. They did not go in for extemporary prayer or, as far as Maycock records, long silent meditations. What they were discovering, along with such luminaries as Lancelot Andrewes, was ‘a sense of the meaning of common worship’ (p.4). Their pattern of life showed how the Prayer Book should be used. At this point, Maycock deserves to be quoted in full:

[T]here was, as yet, no adequate tradition of spiritual teaching in the Anglican Church. In that sense, Nicholas and other English Churchmen of his time were living in a vacuum. They had not been brought into any contact with the new spirituality of the Continent; as yet they knew nothing of the lives of St Teresa, St John of the Cross, St Vincent de Paul, St Francis de Sales, and other great regenerators of the Catholic Church in Europe. . . . [I]n the circumstances of the time, the spiritual isolation of the Church of England was inevitable; and its recovery of tradition was therefore bound to be, in some measure, an academic and empirical process, based upon the reading of books, the study of history and practical experiment. It is this, perhaps, that explains the curious gaps in the professional equipment of the great Caroline Churchmen and the somewhat nebulous quality that occasionally appears in their teaching. (p. 7)

The texture of spirituality at Little Gidding was thus woven out of psalms and hymns, accompanied by the organs installed both in the church and in the house. The Ferrar family were working out what it meant to live the life of the saints, and they seem to have found in that life a deep quality of joy. But was it so joyous, one wonders, for the local children whose education they undertook. After evicting the pigeons from the substantial dovehouse and cleaning it out thoroughly, Nicholas gave his nieces, Mary and Anna Collett, the task of teaching the children to recite the Psalms from memory. These they later repeated to Ferrar’s mother. Some of them will surely have discovered the great treasures of the Psalter. Yet the fact that financial inducement was offered for remembering Psalms correctly when they were summoned to recite to Nicholas suggests a robust and realistic understanding of the child’s mind.

Tim and I have turned to the Psalms as the framework for today’s pilgrimage. There is no hint in Maycock’s biography that the nightly recitation of the whole Psalter, from 9 pm to 1 am, included critical reflection or meditation. The Psalms were taken as a given, and we must assume that they spoke to the situations and experience of those whose turn it was to keep the vigil each night. These things have their own ways of sinking in.

Later biblical scholars have organised the Psalms into categories: Wisdom Psalms, Psalms of Lament, Royal Psalms, Psalms of Ascent, and Psalms of Praise. Those groups will direct the brief meditations at each of the five stations today. If you like, they are little aides mémoires for recalling the complex texture of some extraordinarily holy lives, played out in a time of historical turbulence. They remind us too, that as pilgrims we are also visitors. The Ferrars extended unfailingly courteous hospitality to all, but with great caution. They knew that not all visitors were benign. Even then, some were merely nosey and others came seeking evidence for the practices that Puritan neighbours suspected might be going on. Being a pilgrim means treading very lightly on the past, rejoicing in the stability and inspiration we can find there, but not making ourselves too much at home. Perhaps what we, who speak much more freely and easily of spirituality, will find, is that the past will travel with us, into the futures and communities we are called to create for our own age.

Being a pilgrim is also being a learner, willing to be changed. And so I end with a confession. For years, I have ground my teeth every time a preacher has quoted T.S. Eliot’s instructions about Little Gidding – not to be reported on, but to be recognised as a place “where prayer has been valid”. Walking into this extraordinarily beautiful church earlier, I realised that this was not a high brow-Anglican platitude, even if it is a little over-used. In that place, it is tangibly true.

Dr Bridget Nichols’ and Canon Tim Alban Jones’s addresses at the five stations

Canon Tim Alban Jones’s sermon at Evensong at Little Gidding