In September 2016 Magdalene College, Cambridge, hosted a conference entitled The Ferrars of Little Gidding. This fully-illustrated paper on The Topography of Little Gidding in the Time of the Ferrars was given by the Chair of the Friends, Simon Kershaw. It looks at two old maps from the 16th and 17th centuries and traces what we can see in the landscape of Little Gidding today.

To navigate the paper click on the arrows to move to the next or the previous slide.

In this paper I shall look at what we know about the topography of Little Gidding, focussing on the second quarter of the seventeenth century, when Nicholas Ferrar and his extended family lived there.

I shall look at two main strands:

- first, the more general question of the landscape of the parish, what remains of it, what can be gleaned from these clues, and from the historical record over the centuries.

- Secondly, I shall look at what can be known or inferred or guessed about the two principal buildings – the appearance of the church, and the location and appearance of the manor house in which the family lived.

‘If you came this way, taking the route you would be likely to take’, …

‘If you came this way, taking the route you would be likely to take’, …

‘If you came this way, taking the route you would be likely to take’, …

then you will find yourself out of the fenland of Cambridge, and into the gently rolling Huntingdonshire countryside, the Huntingdonshire Wolds.

The parish of Little Gidding is a broadly rectangular shape with its long axis lying south-west to north-east.

The land rises quite steeply from the south western boundary, formed by the Alconbury Brook, reaching a height or ridge roughly where the modern road to Steeple Gidding and Great Gidding crosses the parish, then falling gently away to another stream before rising again to another ridge at the north-eastern boundary, formed by the Bullock Road.

The majority of the land today is arable, with two smaller areas of pasture where the ground is too steep or too rough to plough and harvest, and a number of small wooded areas and ponds.

There’s a bridge over the Alconbury brook at the south-west of the parish (at the left of the picture), and we can stand there and look around ...

We can stand at the bridge over the Alconbury Brook and look around. The brook is just behind the hedge at the left edge of this picture, and in the distance, not too far away, the hedge up the hill marks the boundary with Great Gidding to the north-west.

We can stand at the bridge over the Alconbury Brook and look around. The brook is just behind the hedge at the left edge of this picture, and in the distance, not too far away, the hedge up the hill marks the boundary with Great Gidding to the north-west.

And we can pan round ...

... and round ...

... and round ...

... and round ...

... and round ...

On the top of the hill we can see the red brick barn, and Ferrar House.

On the top of the hill we can see the red brick barn, and Ferrar House.

The church is behind the trees just to the right of the house.

... keep panning round ...

... keep panning round ...

... keep panning round ...

... keep panning round ...

... The hedge on the hill top marks the boundary with Steeple Gidding ...

... The hedge on the hill top marks the boundary with Steeple Gidding ...

... almost round through 180° ...

... almost round through 180° ...

... And this is the hedge along the brook looking downstream.

... And this is the hedge along the brook looking downstream.

We can climb the hill through a field of sheep.

We can climb the hill through a field of sheep.

This double hedge is interesting. The further hedge is the modern field boundary, and the nearer, intermittent, one is the remains of very much older boundary dating to the 16th century.

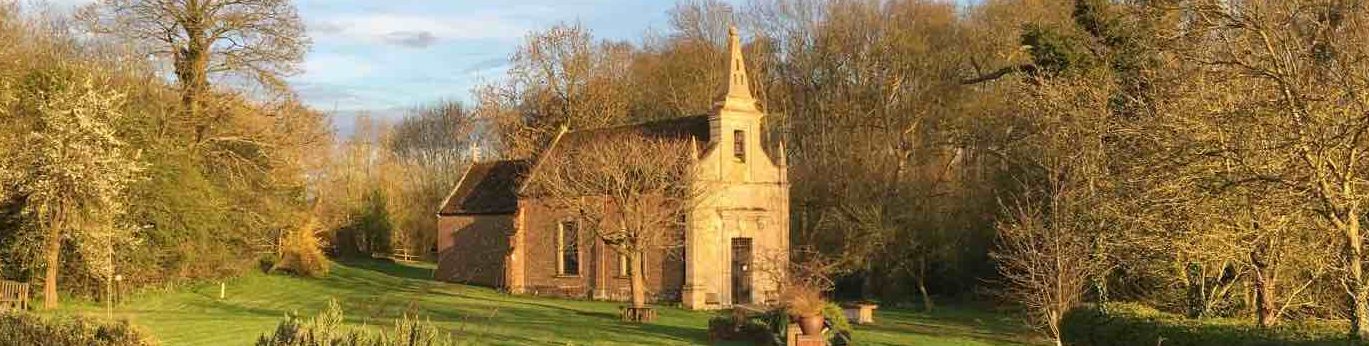

At the top of the hill is the church.

At the top of the hill is the church.

Note the two terraces in the field in front of the church.

This is also a picture of the church. You can just see the south wall of the church through the trees. The land is rough and uneven, and we are 5 or 6 feet below the level of the churchyard.

We can turn around and look back down the hill.

We can turn around and look back down the hill.

We can just see the bridge over the Alconbury brook – it's at the centre of the picture just to the right of the tree, in a gap in the second hedge.

Anyone in the house can clearly see people approaching from a long way off, as the Ferrars did when Charles I called by in 1642.

Continuing north-east, there’s more uneven ground.

Continuing north-east, there’s more uneven ground.

This is a moat, about 6 or 7 feet deep and 90 feet square.

More unevenness. This little valley is the line of the main street of the mediaeval village.

And finally we’re at the top of the hill and can cross the road and look down the hill the other side.

And finally we’re at the top of the hill and can cross the road and look down the hill the other side.

The land falls away to another stream and then climbs to the north-eastern boundary where the Bullock Road runs along the ridge.

That’s Little Gidding now, and the shape of the land itself is pretty much unchanged from the early 17th century. The pattern of usage is a little different.

Little Gidding in 1597 and 1626

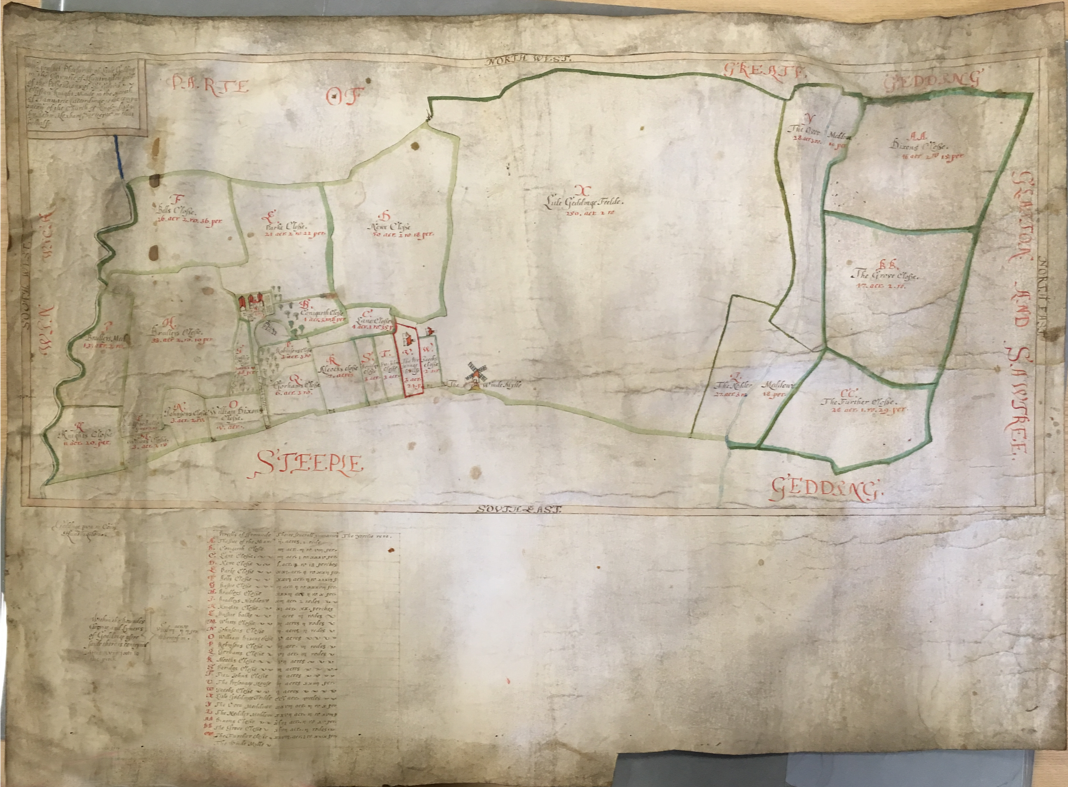

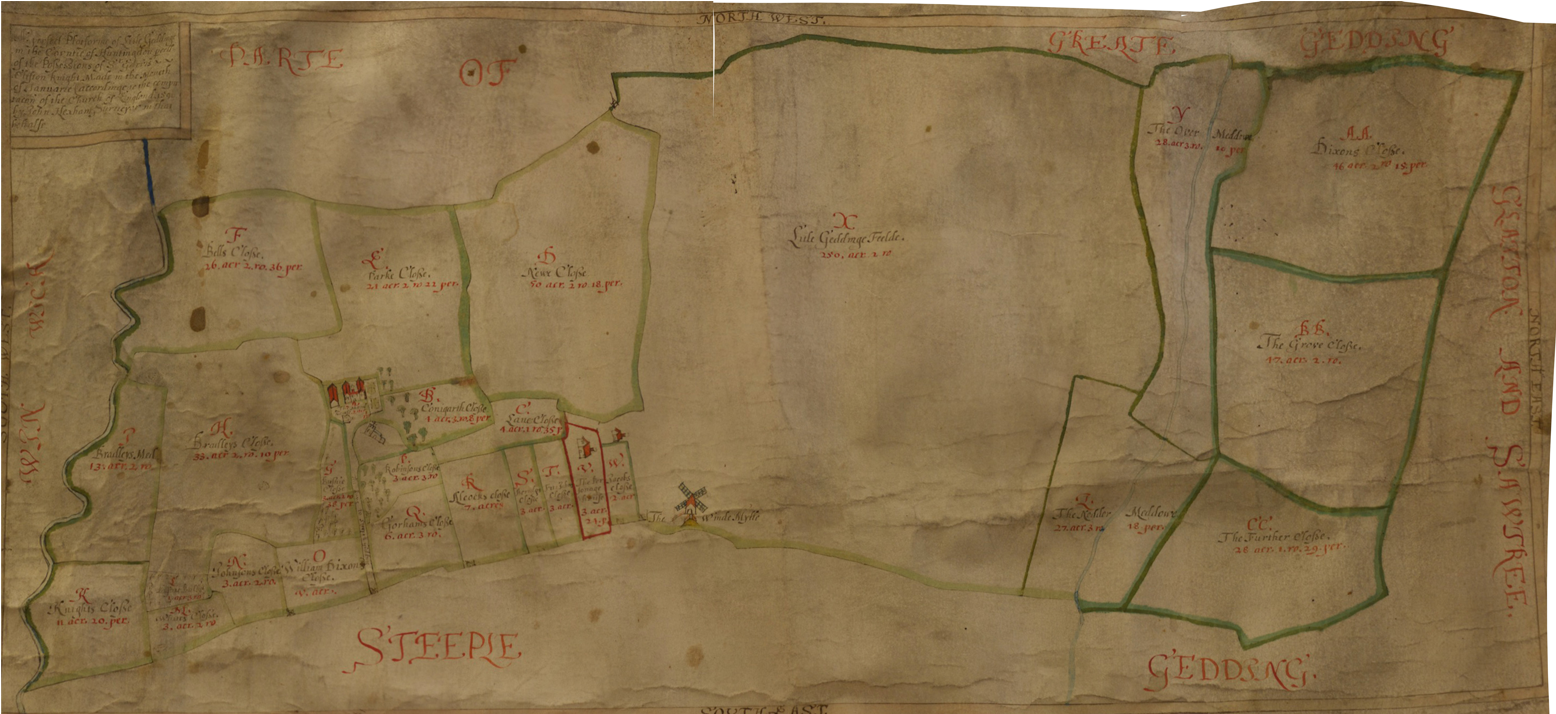

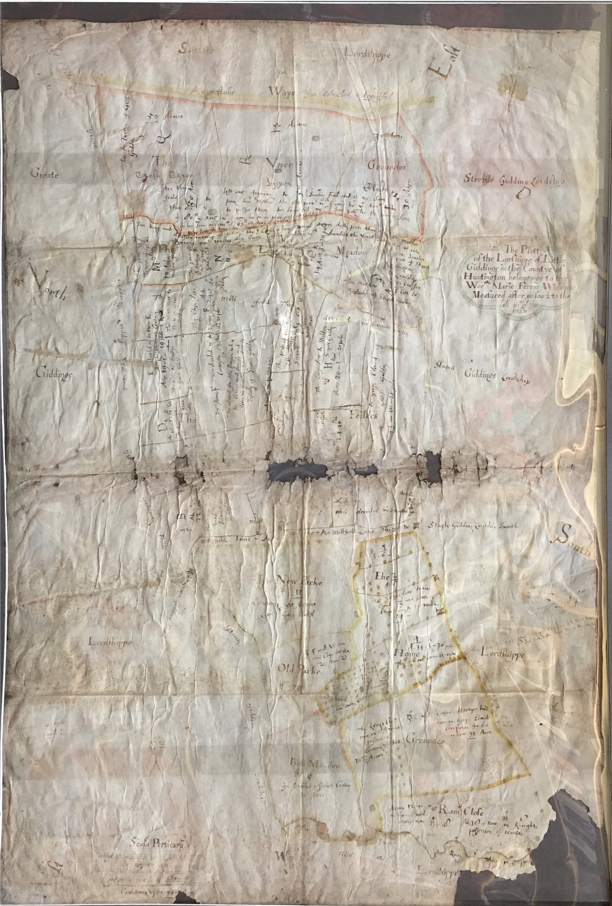

Two maps exist of Little Gidding in the time of the Ferrars. One was made in 1597 by the surveyor John Hexham for Sir Gervase Clifton, who had just bought the manor of Little Gidding. The other was made in 1626 when the Ferrar family acquired the manor. The 1597 map came to light in 2015 and is now in the Huntingdonshire Archives. The 1626 map, by Daniel Hausted, passed down with the estate ownership to the Annesley family, the Viscounts Valentia, and is now in the Oxfordshire History Centre. It is interesting to compare these maps with aerial photography to determine how accurate they are, to compare the current landscape with that of 1597 and 1626, and to see if they shed any light on the location of the house in which the Ferrars lived.

Little Gidding in 1597

First we will look at the 1597 map. It is the work of the surveyor John Hexham, and bears the date January 1596, i.e. January 1597 New Style. Hexham was a reputable surveyor who was commissioned by the Privy Council to make maps of the fens for the drainage projects which were just getting under way. He’s known to have had work through the 1580s, so by 1597 he was an experienced surveyor.

The map was commissioned by Sir Gervase Clifton, a Somerset man born about 1570, who sold his Somerset estate, Barrington Court, and bought the manor of Leighton Bromswold. He subsequently bought other manors in the area and in April 1596 he bought Little Gidding from Humphrey Drewell.

The map was probably commissioned to show the potential income for its new lord. Below the map is a list of tenants and blank spaces for their rents to be entered. The map is made of parchment and it is hard to get it to sit flat to photograph it. Note the curvature at the top left corner.

Little Gidding in 1597

The map itself shows the parish boundary, various fields and water courses, and a handful of buildings: the church, the manor house and the building next to it, another structure between church and house, the windmill, and just two other buildings, one of them labelled “the Personage House”.

Is the building between the house and church the dovecot perhaps?

Only one road is shown on the map: south-east from the manor house, past the church and on to Steeple Gidding. There is no hint of the present road across the parish, nor of any road down to the manor house, nor south towards the Alconbury Brook. Maybe the surveyor or his patron were not interested in roads, only in boundaries, landholdings and potential income.

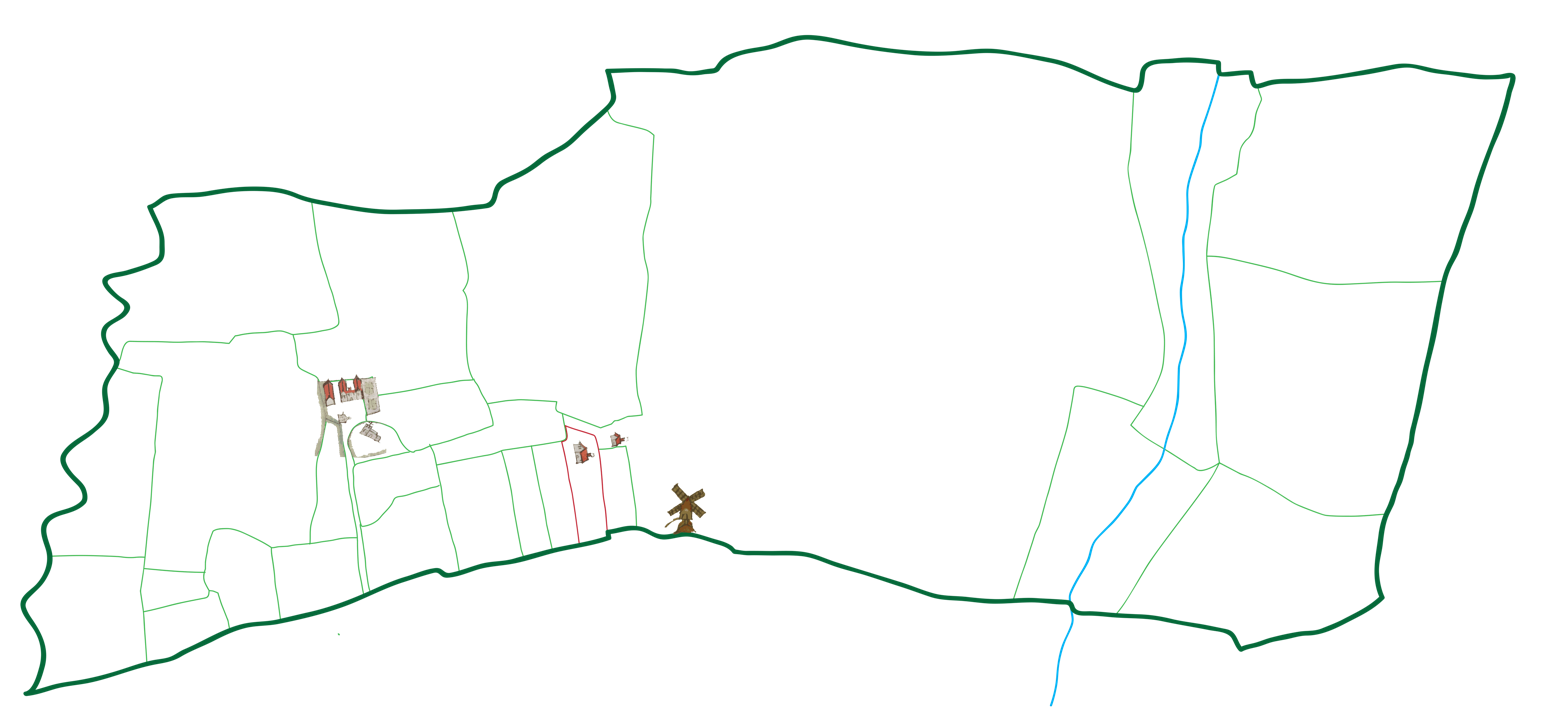

We can trace the parish boundary, fields, streams and other significant features of the landscape to create a clearer drawing...

Little Gidding in 1597

Click on the arrows to compare this outline with the map itself.

Next, we can place this outline on top of the satellite images to see how well it fits...

Little Gidding in 1597

The answer is that it fits very well though not perfectly.

Again, click on the arrows to compare this outline with satellite photograph.

Some of the imperfection is because the photographed map was not lying perfectly flat – see how the top left boundary does not quite align.

The other major non-alignment is at the left where the modern course of the Alconbury brook has been considerably straightened, and the parish boundary with it. The course of the other stream also seems to have been altered.

The overlaying could be improved as well – probably the left most field boundaries should align better with the modern hedges.

But the parish boundaries are highly likely to be in the same place as they were – and with only minor differences we can see that this is so.

We’ll come back to some of the details of this map, but let’s move things forward a few years.

In 1618 Clifton, by then Baron Clifton of Leighton Bromswold, killed himself, and his title and property were inherited by his daughter, who was married to Esmé Stuart, a relative of the king, and Earl of March, who became Duke of Lennox just before his death in 1624.

In 1620 the Earl and Countess sold Little Gidding to Thomas Sheppard, a London merchant and friend of John Ferrar, and the brother of John Ferrar’s first wife Anne.

Little Gidding in 1626

In May 1625 Sheppard sold the manor to Nicholas Ferrar and his cousin Arthur Woodnoth, acting as trustees for Mary Ferrar, paying Sheppard £5500.

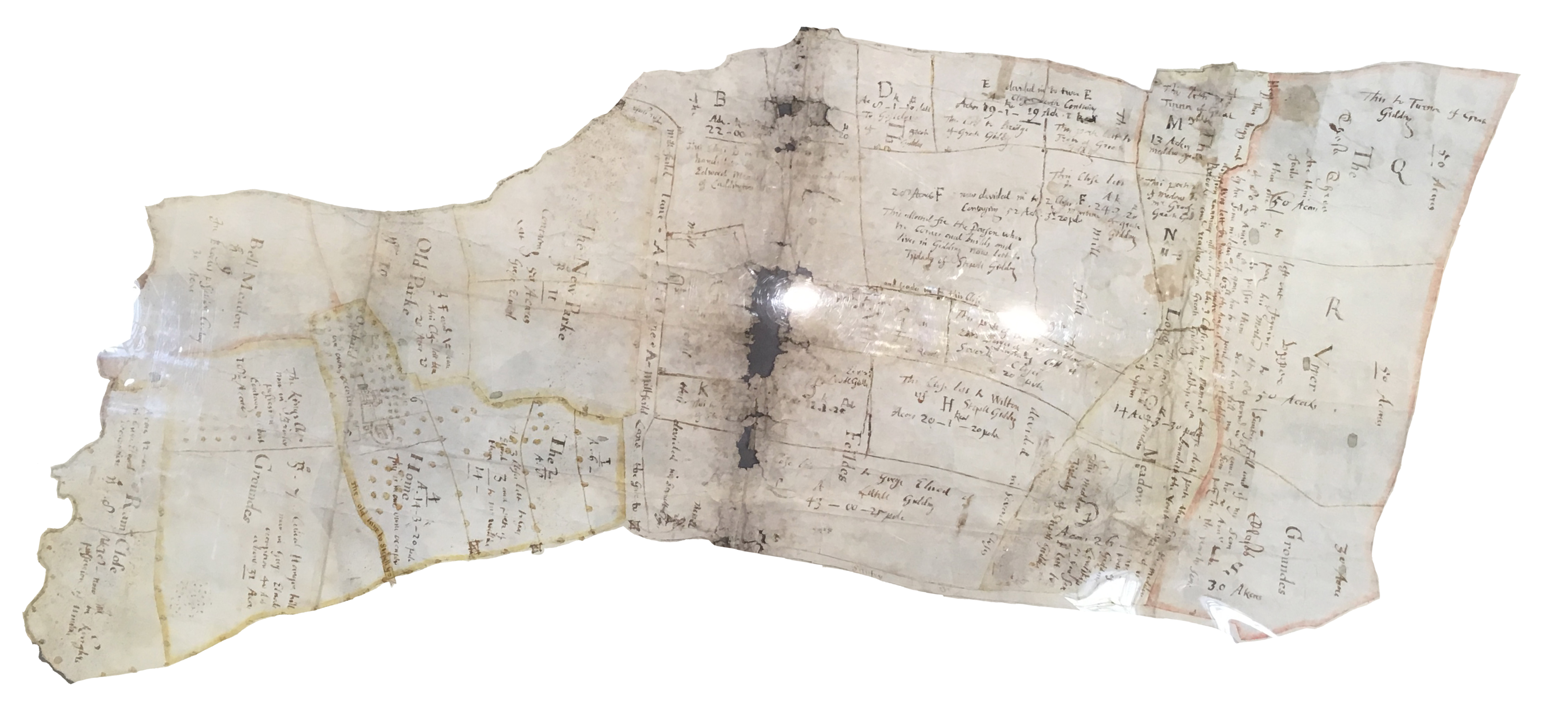

The following year the Ferrars documented their property in a new estate map, now held in the Oxfordshire archives.

The work of one Daniel Hausted, this large map is not in such a good condition as the earlier map, and has been folded in several places which have worn badly. It’s also enclosed in a plastic protective covering that makes it difficult to photograph. However, the important parts of the map are still very clear.

Little Gidding in 1626

Little Gidding in 1626

Here it is re-oriented. There are a number of white blobs – reflections of the lights in the Oxford archives, unfortunately.

We can lay this on top of the satellite images again.

Little Gidding in 1626

Little Gidding in 1626

Again this shows the general accuracy of the map, certainly as far as the boundaries are concerned.

Look at this double hedge. The 1626 boundary follows one of these hedges which is no longer a field boundary. The two corroborate each other – the map explains why there is a hedge there, whilst the hedge indicates the accuracy of the map.

There are even fewer buildings on this map: the house and church are shown, as is the windmill. It does show a number of gates and fences.

Again the map is annotated (in John Ferrar’s own hand, I understand) with the names of tenants. Only the area around the manor house and south-east of the church was kept directly by the Ferrars. Letting it out brought the family an annual income of about £500.

The Ferrars’ predecessors had also depended on rental income and the land was all pasture. The Drewell family owned the estate before Sir Gervase Clifton, and it is recorded in 1549 (when there was a national census of sheep) that Robert Drewell kept 600 sheep at Little Gidding. In 1566 Robert’s son Humphrey Drewell senior cleared away the handful of remaining houses and open strip-fields to create more pasture.

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

We go back, now, to the aerial photographs to see what else they can reveal about the past of Little Gidding.

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

This is the lane down from the road towards Ferrar House which is just off the bottom left of the picture.

At the bottom left we can clearly see an area of ridge and furrow. At the right is the large moated area mentioned before. And between them another uneven area.

This area was surveyed in the 1970s and Brown and Taylor reported their findings with another map.

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

Toggle back and forth a few times to see the overlay.

This area is the remains of the main street of the mediaeval village, which consisted of the street, and houses on each side, represented by these closes, and beyond that the village fields farmed as strips probably right up to 1566, and preserved here because the area has never been ploughed.

We can zoom out a little ...

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

Little Gidding: the shape of the land

Here we can see all the field alongside the lane down to the church and the wooded areas east of the church.

The line of the mediaeval street passes through the wooded area, round to the south of the church where it splits in two. One branch heads towards Steeple Gidding, and the other down the hill towards the Alconbury brook.

We’ll come back and look at some other terraces up near Ferrar House.

The moated area at the north-east is universally described as a “homestead moat” and “presumably the site of the medieval manor house”. Maycock comments that “when the house was built or demolished, who lived in it, what it looked like” cannot be answered. The Victoria County History presumes that it was the manor house of the Norman landlords, the Engaines.

The maps of 1597 and 1626 show none of these earthworks, but on the 1597 map the exact site of the moat is occupied by a house labelled “The Personage house” together with a conventional sketch of a two-storey house with a single chimney.

The 1626 map shows nothing here and further investigation is needed.

|

|

| 1597 | 1626 |

Pictures of the Church

In all this, the location of the church is a fixed point.

But what did it look like?

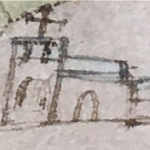

The two maps both show the church. We have seen how accurate the boundaries are – can we trust the images of the church?

The pictures in the two maps are broadly compatible.

Each shows the building from the south side with a west tower. The tower shown in the 1626 map is definitely square (or rectangular), that in the 1597 map probably square but not necessarily so.

Each map shows a south door, which would have been of little use to the Ferrars, whose house was to the north, and who entered the church through the west door. But a south door is consistent with the mediaeval village, whose main street passed to the south of the churchyard. And the 1626 map shows a gate out of the south of the churchyard, where there is still a gate to nowhere.

So much for the similarities.

The 1597 map shows what might be a south aisle, and it also has a small eastward extension, presumably a chancel. John Ferrar describes a north aisle or transept but does not mention a south aisle. The tower in the 1626 map is perhaps a little taller.

And we can make one more speculative deduction: in the 1597 map the church is white or grey, and we can infer that it was built of stone, unlike the present building.

There’s another well-known picture associated with Little Gidding church ...

|

|

|

| 1597 | 1626 | 1641 |

Pictures of the Church

The woodcut on the title page of The Arminian Nunnery was published in 1641.

John Ferrar mentions it, condemning the scurrilous contents, but doesn’t complain about the picture of the church itself. Lots of people have discussed whether or not it is realistic, but Leslie Craig in 1950 argued convincingly that it is a copy of another engraving with hills in the background, and suggests it might be Italian in origin. So we will ignore this picture.

And there’s a fourth picture, a tiny thumbnail ...

|

|

|

|

| 1597 | 1626 | 1641 | 1604 |

Pictures of the Church

This is a photo of an illustration in the VCH of a map of 1604 of the Fenland bearing the signature of Robert Cotton and now in the British Library.

It contains distinct images of all the churches in the area from St Neots to Whittlesey and across to Ely. There is some indication of accuracy. Steeple Gidding church is shown with a spire, for example. For what it’s worth this illustration is compatible with the other two.

Interestingly all three show a large cross on top of the tower. The 1604 map does not show such a cross on every church so perhaps it is not just a map symbol.

The House in 1597

And what of the Manor House?

Here we don’t even know the site, let alone what it looked like.

Our starting point again is to overlay the old maps onto modern images and maps. We can also consider the earthworks and contours and other evidence.

Here is an aerial photograph of Ferrar House. It’s turned through 90° compared with the earlier slides, so the lane from the house to the road goes up the image.

The House in 1597

This is the 1597 map overlayed onto the satellite photograph.

We can align the parish and field boundaries. The church is perfectly oriented. The churchyard boundaries are pretty good.

The road to Steeple Gidding possibly coincides with the mediaeval street.

The house faces south-east towards the church. There is a formal garden across the current site of the farm buildings and Ferrar House. The house itself is simple and formal.

And there’s another building to the south-west.

The House in 1626

The 1626 map can also be aligned quite accurately ...

The House in 1626

The 1626 map can also be aligned quite accurately. Note for example how the 1626 field boundary north of the house crosses a modern field – but corresponds quite precisely with a mark in the photograph.

Move back and forth between the slides a few times to compare the images in this and the previous slide.

Also the churchyard boundary, both the straight line between church and house, and the ring of trees on the other sides;

the series of three ponds, north-west of the house on the map, sit precisely over the modern equivalents.

The two boundaries between the house and church align very well with the modern retaining wall in the garden of Ferrar House, and with a ridge or mark on the ground.

On the other hand the church is in the right place but its orientation is not correct. It may possibly have been drawn at an angle that displays better with the orientation of the map.

With these key alignments, the house is shown straddling the end of the modern lane and overlapping Ferrar House and into the field. This image of the house is somewhat different from that in 1597. It seems to be a jumbled courtyard of buildings.

The freestanding building south-west of the house in 1597 is not shown, but maybe it had become derelict and been demolished.

One wing overlaps with the present Ferrar House, which would make it conceivable that some of the manor house survives in the present Ferrar House. Skipton in 1921 writes “When I first visited Little Gidding many years ago, before the farmhouse had been refaced and remodelled … the entrance … opened into … a charming wainscotted hall”.

The House in 1597 and 1626

We can compare the two overlays, and see that the conclusions are slightly different.

It’s all a bit tentative, and we could probably have pushed the image of the 1597 map slightly up and across which would bring them into closer agreement.

We still have to face the discrepancy in the appearance of the buildings, and I haven’t got any answer to that.

But there are two more snippets to consider.

The House in 1626

First, the earthwork survey from 1977.

Just into the field, away from Ferrar House is a terrace, which we saw from the ground in one of pictures at the start.

This terrace coincides exactly with the garden area in the 1626 map.

A magnetometry survey in 2008 instigated by Trevor Cooper found “some interesting rectilinear forms” and suggests these may be “paths and/or terracing walls in a formal garden”. In this alignment, the house sits on part of a wider terrace.

And secondly there’s a sketch of ...

The House in 1798

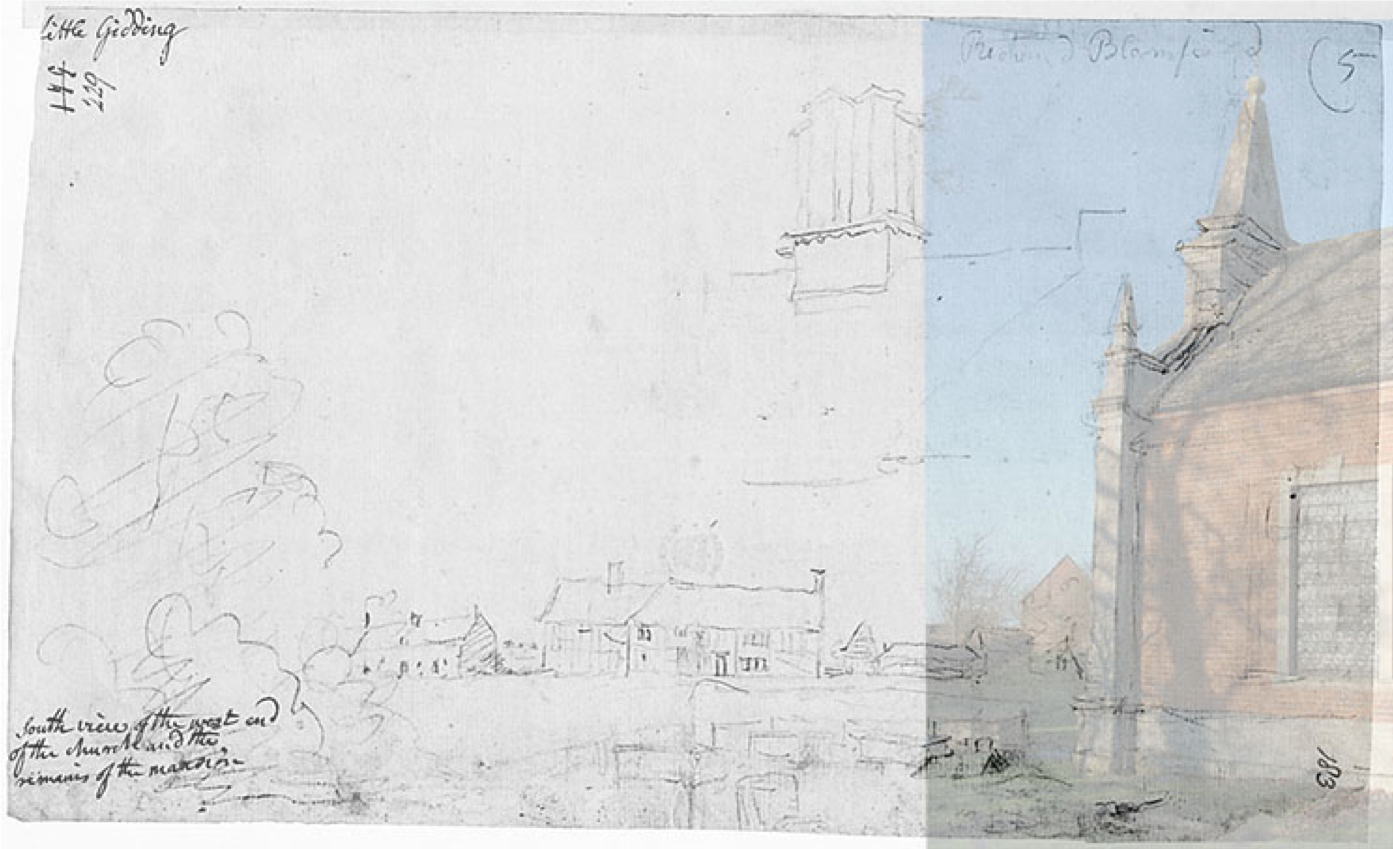

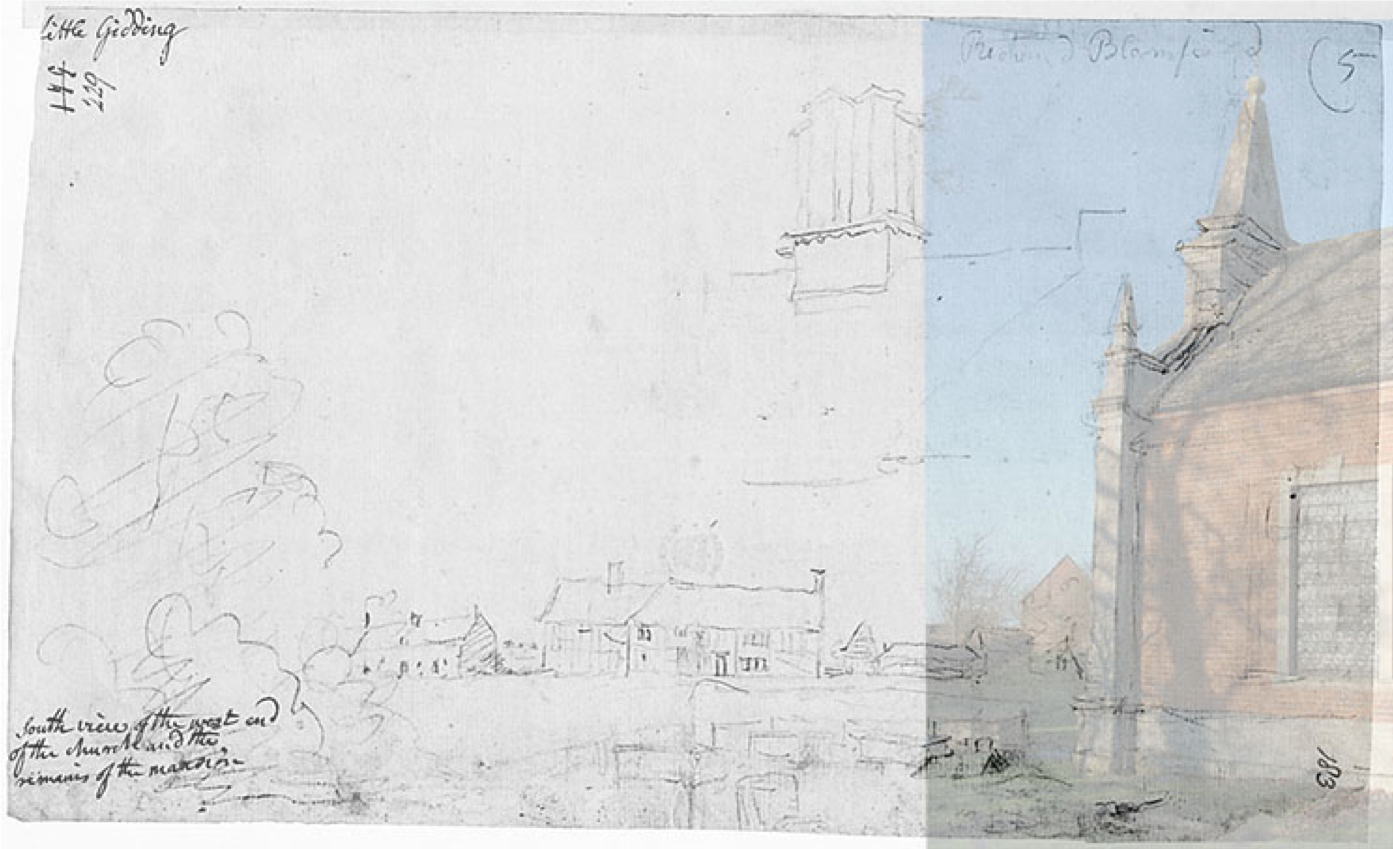

And secondly there’s a sketch of 1798.

It’s by the antiquary and draughtsman-cum-architect John Carter, and is among a significant collection of drawings of Little Gidding made by him in 1798. It shows the church from the south, and to the left some houses, with a detail of some chimneys above. The caption is “south view of the west end of the church and the remains of the mansion”.

Is it one drawing showing house and church? Or is it two separate drawings with no immediate relationship between them?

We can stand in the place Carter stood and see what we can see.

The House in 1798

If we place this photo behind the sketch we see that it’s a very good match. It must be very close indeed to where Carter stood to draw the church.

Further to the left the modern view is obscured by trees through which you can just make out the lie of the land on the hill and terraces.

We have one more piece of evidence ...

The House in 1798

And that’s this 1886 OS-map at 25 inches to the mile.

In the field is a row of buildings, possibly 4 cottages (with gardens behind them, not shown on this map, but they are on another edition). These are plausibly in the right place to be on the site of the cottages at the left of Carter’s drawing. If so that would confirm that this is a single drawing and we can see where it would place the other block.

Is that block one building or two? We can compare it with the images on the maps.

The House in 1798

And that’s this 1886 OS-map at 25 inches to the mile.

In the field is a row of buildings, possibly 4 cottages (with gardens behind them, not shown on this map, but they are on another edition). These are plausibly in the right place to be on the site of the cottages at the left of Carter’s drawing. If so that would confirm that this is a single drawing and we can see where it would place the other block.

Is that block one building or two? We can compare it with the images on the maps.

Here’s the 1626 image. Look at the roof lines of the wing at the lower right.

Does that suggest this roof on Carter’s drawing? At least we can say that it is compatible.

Conclusions

It’s hard to conclude with any certainty.

Both maps seem pretty accurate. Their depictions of the church are compatible.

But their depictions of the house are different in position, orientation and appearance.

I started by thinking that the newly-discovered 1597 map would answer questions and prove more accurate. But I cannot conclude that and further research is needed. Perhaps there are more maps or depictions still to come to light.

We are tantalisingly close to the answers. But as it was for Tantalus, the fruit is still just out of reach.