Stephen Conway, the Bishop of Ely and President of the Friends of Little Gidding, led the annual celebration and commemoration of Nicholas Ferrar Day at Little Gidding on Saturday 7 December 2013. After the service he addressed those gathered, linking the life and example of Nicholas and his family with the recently-adopted Ely diocesan vision statement.

We pray to be generous and visible people of Jesus Christ. He calls us to discover together the transforming presence of God in our lives and in every community.

This has recently become the Diocesan Vision, adopted by the Bishop’s Council. We now have to live it out at every level. In the process of developing the vision, there was some heated discussion around whether we should use an indicative statement, namely, “we are the generous and visible people of Jesus Christ”. In branding terms in large commercial organisations, an indicative statement would be de rigueur. Some of our number were happy with an indicative statement; but most were conscious that the world at large would find a statement laughable, in relation to, say, the failure to vote for women. An indicative statement would be laughable or plainly untrue so far as most people in our society would understand. Archbishop Justin spoke in his presidential address last July about the social revolution which had been brought home to him when he spoke in the House of Lords against equal marriage and what he experienced was not a feisty debate: he was ignored.

In the face of this, I decided to road test our proposed vision statement among some atheist and agnostic friends – it is good for a bishop to have some. It was one such friend who confirmed that the indicative statement was ludicrous on its own. No one under 35 would bother even to listen. What would make the difference, so far as he was concerned, was to preface the statement with a reference to prayer. “After all,” my friend said, “that is what you Christians do, isn’t it? What is more, lots of people who do not claim to be religious say that they pray regularly.” I thought immediately of my much younger sister who spends a fortune on candles which she lights in quiet spaces and offers intercession very regularly, even though I could count on my fingers the number of times she has been in church in her adult life. For me, certainly, putting “We pray to…” in front of the statement began to ring true of a more humble Church, seeking grace first, rather than making claims for ourselves.

Any vision statement claims antecedents and agreement from our forebears and I wonder seriously whether I am on a good tack by claiming the Ferrars and the Little Gidding Community in support of the vision. In 1657, with John Ferrar’s death, the original community died and its survivors drifted into obscurity. Nonetheless, the vivid but short life of that community came alive again in the imagination of Christians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and has stayed resilient.

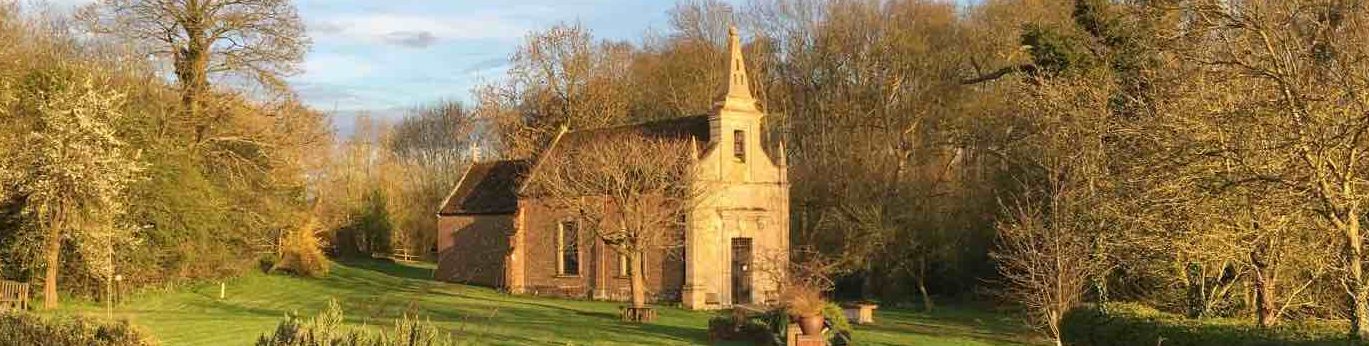

“Little Gidding” was the last of the Quartets of T S Eliot to be written. It appeared in print in 1942 and is revealed as the place where the problems of time and human fallibility are redeemed. In the initial portion, Eliot paints the word picture of a bright winter’s day, where everything is blighted yet aflame with the sun’s fire. Eliot reflects on those who visit the community and come only “to kneel / Where prayer has been valid.” It is here that man can encounter the “intersection of the timeless” with the present moment. The final section of the poem, and of the whole of the Quartets, brings the spiritual and the aesthetic together in a final reconciliation. Perfect language results in poetry in which every word and every phrase is “an end and a beginning.” The timeless and the time-bound are interchangeable and in the moment, if one is in the right place, like the chapel here, all will be well.

With that backdrop, I am keen to claim a connection between the new diocesan Vision and the original community of Little Gidding. Here we are in a place where we are confident that prayer has been valid. This is not to claim it as a shrine as such; but my experience of visiting lots of holy places is that they are made holy always by the action of God’s grace and by the depth of the prayer of human beings who love God. Before the terrible war which destroyed Yugoslavia, I visited Bosnia to be a pilgrim at Our Lady’s alleged shrine at Medjugorje. It was phenomenally tacky. An Irishman with whom I struck up a friendship assured me that he had seen a fellow countryman sporting a t-shirt with the legend, ‘Through Jesus to Mary’. I never saw such a shirt or person. What struck me most was the holiness of the nondescript tent in which the Blessed Sacrament was perpetually exposed for devotion on a pile of bricks. For all the tackiness of the stalls and shops, one was deeply aware that underneath everything was a deep surge of prayer. Here in Little Gidding is a place where we can confidently say that we pray to be vehicles of God’s presence in the world.

The danger attached to some notions of the life of Little Gidding in the seventeenth century is to think that it was some version of a monastery as it was attacked by the puritans for being – that ‘Arminian nunnery’. Western spirituality in the twentieth century and up to now has been bedevilled by the presumption that praying like monks and nuns is all that really counts in the end. This is a great fallacy, most vigorously countered by monks and nuns. We need to learn how to pray in a real context, where we actually live and have our being, not in some idealised state. The interesting situation with regard to the Ferrar/Colet community is that it was not much different on the surface from the godly homes of East Anglian puritan gentry who from time to time established seminaries of young men considering the sacred ministry. The key difference lived by the Community at Little Gidding was its intention of permanence. However it may have been excoriated by its association with Archbishop Laud and King Charles I himself, it was essentially a sober, Prayer Book community seeking to live Acts 2 as a Christian body holding all things in common, as we have heard ion our second reading at the Eucharist this morning. They were Reformed Christians like their neighbours, like Ferrar’s inspiring model, George Herbert, at Leighton Bromswold. Their model for most of their worship was Lancelot Andrewes, a translator of the Authorised Version and a favourite bishop of James I.

The Virginia Company had unexpectedly soaked up all their resources and deeply changed the expectations of this family about their future. Rather than rail against it, they saw the hand of Providence and, sooner than expected, took themselves to the ruined manor of Little Gidding and set about making it work. While Nicholas set about devising their pattern of devotion, his mother, Mary, made the place work. As we seek to pray ourselves into a vision of our future under God, I am struck by the groundedness of the witness of this place. Precisely what we do not see is some kind of monastic Rule, laying the law down. What we see is a rich pattern set by seeking to live the life provided by the Book of Common Prayer in the practical reality of a house that needed complete and loving restoration. When we pray for the power and guidance of God’s Holy Spirit to accomplish anything, it is not some esoteric, gnostic seeking after being special through what we know in secret. We pray to be more and more human and down to earth, precisely so that we can be heavenly minded.

What we learn from this Community is not rule but pattern of a calling lived in the rhythm of the Book of Common Prayer. In our modern times and with Common Worship we can forget what a revolution Cranmer’s book created. The radical shift was not just to have the Bible and worship in the vernacular; but for the Divine Office to break free of clergy and the cloister as a burden of offices piling up on one another, as Luther the Augustinian Friar perfectionist received it, but as the daily rhythm offered to all, especially the laity. Nicholas Ferrar got himself ordained deacon at Westminster Abbey by Laud to signify his being set aside for holy duty; but the commitment to the daily round of BCP plus hourly prayers on a rota and, later, night prayers inspired by Herbert was largely a lay commitment and entirely so after his death when John assumed leadership of the Community. One of our key goals as a diocese is to develop further the active and equal partnership of laity and clergy together. We see this exemplified both in the Community of the seventeenth century and in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. What excites me is the witness to a pattern of praying and living which was genuinely lay led and cross-generational, with high expectations of the spirituality of children and young people. This viable pattern of worship and work also allowed sensibly for exercise and leisure. It was a pattern of godly and human well-being which is to be imitated.

One of the drawbacks of any vision is that it can sound alright but have no basis in the story of the communities involved. The sharp reminder from the lived experience of the Community at Little Gidding is that the real vision is supplied by the overriding narrative or story which defines the whole. Our Community was famous in its own lifetime for its production of concordances and gospel harmonies which enabled the reader or listener to encounter a united narrative of our story as Christians in the gospel. Of course, the different emphases and theologies of the gospel writers is very important; but more important still is what does the whole trust of the story from Jesus’s birth to his resurrection do to us. We as Christians are certainly not unique for being generous: what makes us unique is our understanding that the story of our lives is completely interwoven with God’s story of redemption. This is what it means to discover the transforming presence of Jesus Christ in ourselves and every community in which we have a stake as worshippers and citizens.

Mary Ferrar and her other son, John, set out to guarantee genuine hospitality to visitors and local people alike. This was not a community which prayed, but a community fashioned by prayer to be generous and welcoming. There was a particular commitment to the holistic education of local children which was demanding in terms of reciting psalms and learning and also generous in terms of providing wholesome meals and warm clothing. We have 83 church schools in the Diocese at the moment. We are likely to acquire more as new communities develop. This is one conspicuous example of what it is to be so transformed by the gospel story that we seek to be both generous and even more visible in the service of our communities, recognising that our schools have huge potential to be ecclesial communities, primed for inter-generational mission to children, parents, teachers, governors, grandparents and business sponsors. Like the Community at Little Gidding, we need to be demanding of ourselves so that ethos and standards are indivisible. We also need to embrace with some courage the need to be distinctive and visible in the hurly-burly of education policy and in the determination to sustain faith schools as places where we do not have to assume the casual secularism of the general culture lived by young people.

Coming to Little Gidding today, one is conscious of arriving in a desert place. Of course, this is not Sinai or the Judaean Desert which some of us have sampled as pilgrims. I am thinking more of the medieval French idea of a desert as a lonely place away from the usual routes and centres of interest, places where saints established themselves and to which then pilgrims were drawn. We are in the part of the Diocese which probably feels furthest away from Ely and the diocesan office. Nonetheless, the Bishop is here and I should say that Little Gidding continues to be one of those thin places where the Spirit of God feels especially close. Our vision speaks about our being visible. An adult was taken aback and said how could we not be visible; but it took a child to understand that it is all too easy to make ourselves invisible and to collude with the world that religion is a privatised thing which, in a post-modern world view, is just about tolerating novelty so long as it is harmless. When the Ferrars were here it was even more remote than now; but the King visited at least twice. It was a Laudian experiment in Cromwell’s East Anglia. It was a brave enough community to return from exile and last another ten years. We have to work at remaining visible and engaging with the world as it is, all around us. Being a praying community is precisely what makes us some earthly use. I have never known people more switched onto what is going on in the world than contemplative nuns and brothers. King Charles was very keen that the Community should send him its rendition of the Books of the Kings. I wonder what they dared to say to their anointed king and devout protector of the Prayer Book about the reflection on kingship and prophecy in those books. Just as Herbert withdrew from the patronage of the royal court, so the Ferrars gave up the equivalent of running a FTSE 100 company to sweep the floors here. We must be alert to the challenges to be visible in the public square today. Nowhere is remote from the public life and choices of human beings. We are properly thanking God for the courage and generosity of Nelson Mandela. The struggle against apartheid, of course, involved communists and others who had no time for organised religion; but the home of the struggle was in the churches. This is why there came to be a truth and reconciliation commission rather than retributive kangaroo courts when apartheid fell. the Berlin Wall came down when the Church in East Germany determined to be the praying place of protest. In the hierarchy of saints, we would number Ferrar among the confessors. It was the Confessing Church whose members like Bonhoeffer sacrificed themselves in the struggle against Hitler. We need to be at every level a confessing Church now, not because we are persecuted but because God wants us to proclaim his kingdom.

Our gospel reading told us the story of the call of Matthew. The Caravaggio painting of the same presents us with Matthew as a seated figure whose hand gesture suggests that when faced by Jesus telling him to follow he says, “Who, me?” in the picture, Jesus assumes the answer is yes and is already turning to leave. Other figures in the painting seem oblivious to the presence of Jesus and carry on counting their money. The Ferrars and Colets actively responded to God’s call upon their lives and did not hold back. For Nicholas it was not a long-lived calling and the Community faced trials and changes that they could never have predicted. But they were faithful. We know in our own experience how easy it would be to go on counting our own concerns and this applies as much to bishops as to anyone else. Nonetheless, there is a constantly held out invitation from Christ to accept the invitation to be a disciple who is formed in community in a parish or other context. The seventeenth century was as fascinated by virtue and character as we are in the twenty-first. The Ferrars had a godly vision of living a life which inhabited the character of Christ. They sought to be a family and friends under God whose learning about what that might mean would be helpful to others. In 2013 we claim to be their friends and to share a heavenly vision with them because we, too, pray for the coming of God’s kingdom right here.