On Trinity Sunday 1626 Nicholas Ferrar was ordained Deacon in Westminster Abbey. On Trinity Sunday 2012, the Revd Vernon White, Canon Theologian at Westminster Abbey, and an old member of Clare College Cambridge (Nicholas Ferrar’s own college) preached this sermon at a service at Clare, attended by many members of the Friends.

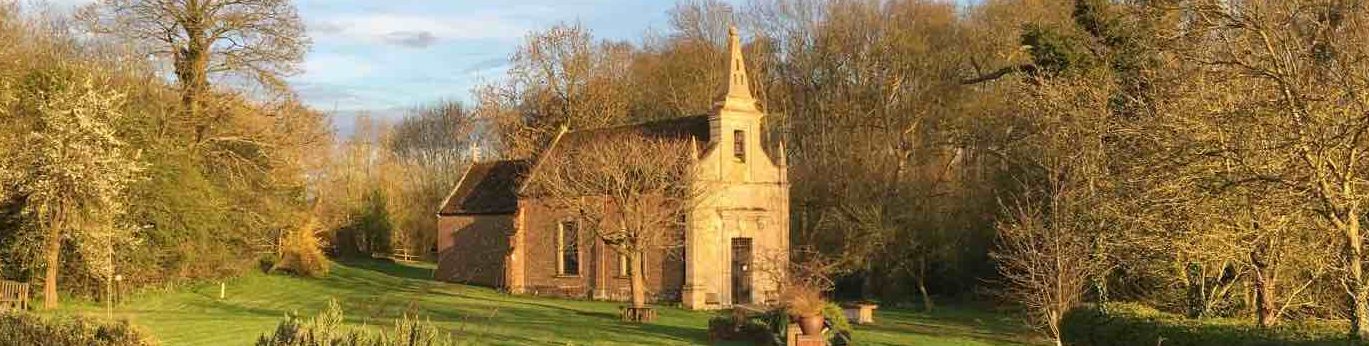

In 1625 the Huntingdon village of Little Gidding welcomed the arrival of its new resident, Nicholas Ferrar. He moved in after abandoning an academic career. A strange decision, you might think, when what he had left was the incomparable advantage and honour of being a Fellow of Clare! But then he’d also abandoned a successful business career in a City trading company. So clearly something was afoot in this man’s soul. And it was. He had turned his back on more obvious careers to be ordained to the relatively lowly role of deacon: and in the middle of what were religiously and politically turbulent and dangerous times, he and his family had come to this village to establish a unique way of living in community. Unique because it transcended the religious divisions. It didn’t follow conventional catholic monastic rules – but nor was it simply an extended version of pious protestant family life: they followed a daily discipline of contemplative prayer and psalm reading, but it was more porous, informal, than a traditional monastic order – and they were always deeply immersed in the wider community as well, teaching the poor and caring for the sick. It attracted interest. The poet George Herbert visited the house. Charles 1 too. And although Cromwell’s men then paid a less friendly visit, what the community finally became was an extraordinary symbol of reconciliation. A reconciliation between apparent opposites: political reconciliation between King and Parliament; religious reconciliation between catholic and protestant: spiritual reconciliation between withdrawal from life, and engagement with life.

As you may know, TS Eliot celebrated this in his final quartet, ‘Little Gidding’ – a poem which blends images of apparent polar opposites into single transcendent truths. It begins with the paradox of ‘midwinter spring’, a season which subverts time, transcending the conflicts between past and present. It ends with reconciliation of more radical opposites. Against the backdrop of blitzed London, a dove descends with ‘flame and terror’. It is an image of a dive bomber – yet still a dove, the Holy Spirit. How so? How could ‘love’ devise ‘torment’? Is it really possible that God is bringing even these worst evils into some final good? Incredibly, yes: ‘all shall be well, all manner of thing shall be well’, the poem ends, quoting Julian of Norwich’s astonishing prophecy.

But we don’t just have to jump to Eliot and the twentieth century to find Ferrar interpreted this way. We only have to move from Little Gidding to the banks of the River Lea in Hertfordshire, and the gentler writings of his contemporary, Izaak Walton. He too had withdrawn from the immediate turmoil of politics, civil and religious conflict. It was a more solitary withdrawal. He spent time fishing. But with a similar outcome. He too sensed resolution beneath turmoil. In the endless movements of water, wind in trees, flickering light on the ripples, he found a kind of permanence: an intimation of final harmony beneath the moving surface of things. Not surprisingly he mentions Ferrar admiringly in his writings. They had much in common.

But were they right? Is the harmony of Little Gidding and the River Lea the real truth about life? Were Eliot’s later more agonistic visions of ultimate reconciliation really true? Or were they all just escaping from the reality of life which at bottom will always be conflicted, ragged, unresolved? It’s the old conundrum about all religion, and much philosophy: is it simply because ‘humankind cannot bear very much reality’ that we create these visions of a final harmony? The fact they come about through withdrawal might make us wary. It’s easy to weave spells in places of rural quiet and beauty, with the sound of running water, or for that matter in religious ceremonies with the sound of glorious music. Easy in those moods to make reality fit a higher and more serene outcome and evade what life is really like. Preachers, monks, fisherman, poets and philosophers alike – we all need to beware of that.

Yet even duly warned, I note this. I note it was in a quiet time and place, as we heard in the Gospel, that Nicodemus came to Jesus to really learn about life. I note Jesus own withdrawal to desert places, at times, to find his ultimate spiritual orientation and mission in life. I note that prophets before him found their hope and energy and belief in desert places. I remember my own brief foray into the Judaean wilderness, which seemed not so much an escape but an encounter: the apparently empty landscape strangely full, connected, at harmony, in itself, with its observers, and with God. A complete contrast to the ostensibly real world of East Jerusalem from which I had just come, with its disorientating cauldron of competing sights, sounds, cultures, commerce, religions, politics – yet it was the desert which seemed more real.

But it’s not my experience which should carry weight: it is Christ’s experience which is ultimately so telling. He lived the conviction that there is a divine purpose and unity in all things – in a reality as conflicted for him as it is for us. He lived and died reconciling conflicted people to each other and to God; and his resurrection vindicated that life. St Paul was utterly convinced: ‘in Christ all things in heaven and on earth are reconciled’, he wrote. And if it sometimes takes withdrawal to grasp this, why should that invalidate it, when Christ too withdrew? Especially since his withdrawal from the clamour was so clearly not just escape, not burying his head in the sand – for it always sent him right back into the world, a sure mark of authenticity…

When like Ferrar you leave Cambridge, or even if you don’t, be sure to attend to your soul. Do not lose vision. Find some regular desert place, some fishing place, literal or metaphorical, where the Spirit of God can keep finding you – to help you to see past the clamour, to remind you what is ‘really real’. Being here in this service may mean you have already sensed this is important. You have realized that the spell of music, a tranquil setting, a supporting community, the power of scriptural stories, the mysteries of sacraments, are at best not just escape or fantasy but a kind of desert: a gateway to decluttering our life in order to see God and the world more clearly, and act in it more truly. Keep hold, then, of these rhythms of public religion which help in this way. But also, seek out such gateways not just in church but in the rest of your life too: in a private rhythm of prayer, or contemplative activity, or regular meeting with a soul friend. It is not escape: it’s a path to truth. It is how God will keep your soul alive, whatever you do in the world…