Stephen Conway, the Bishop of Ely, and President of the Friends of Little Gidding was leader of this year’s Pilgrimage on 19 May, preaching at the morning eucharist at Leighton Bromswold, giving reflections at the the five stations on the Pilgrimage Walk, and preaching again at Evensong at Little Gidding. This is the sermon he preached to a packed church at Evensong.

Stephen Conway, the Bishop of Ely, and President of the Friends of Little Gidding was leader of this year’s Pilgrimage on 19 May, preaching at the morning eucharist at Leighton Bromswold, giving reflections at the the five stations on the Pilgrimage Walk, and preaching again at Evensong at Little Gidding. This is the sermon he preached to a packed church at Evensong.

This morning we were worshipping in a church closely associated with George Herbert but the building of which he probably did not much see. Here we are at Little Gidding so closely associated with TS Eliot but which he only visited once in 1936.

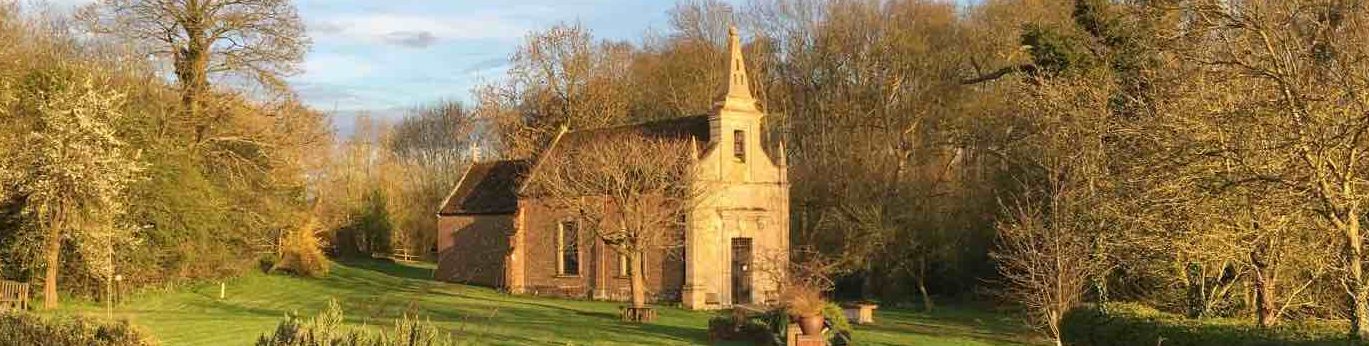

His poem ‘Little Gidding’ the last of the Four Quartets is rooted in the physical reality of this place, nonetheless. The poem plays with the common Eliot theme of past, present and future all coming together but, however you get here, you still turn behind the pig-sty to the dull façade and the tombstone.

The tombstone is the reminder that what drew Eliot and draws us is the life and witness of Nicholas Ferrar and his household who formed an ascetic community of prayer and service here for twenty years, the only experiment in such a life between the Reformation and the mid 19th Century in the Church of England. Dismissed by suspicious puritans as an Arminian Nunnery, it was a community which sought to live the sober but rich rhythm of life set out in the BCP. I have recently been teaching in a clergy school in the Church of Sweden. Because of a continuing church tax, parishes are very well funded and have a significant number of clergy for every parish, with a regular weekend off. None of you is allowed to leave and go there! In a very different culture indeed, it is likely that Ferrar devoted out time to what we would call recreation. What he sought to model is what later William Law called the serious call to the devout life. Leaving behind the Virginia company and a future at court, Nicholas Ferrar, like George Herbert, realised that the urgent call was to serve the God who is directly connected with this world as if by a ladder, that ladder being Christ himself.

Nicholas Ferrar and Little Gidding was a focus of the hatred of the Puritans. He was widely associated with Archbishop Laud who ordained him in 1626 while still Bishop of St David’s and was seen to be part of that ‘advanced’ Catholic party within the Caroline Church. This was not surprising given Nicholas Ferrar’s travels around Europe from 1613-18 and his encounter with every conceivable religious tradition.

Nevertheless, it is a bitter irony that the Puritans who dispersed this community finally in 1646 shared so much with the Little Gidding community in their conviction about the breaking in right now of the Kingdom of God. Modern Puritanism is sometimes described as a form of dispersed monasticism, seeking to model a distilled and ordered form of ascetic Christianity in an idolatrous and dangerous world.

Little Gidding was that kind of distilled and ordered life in Christianity in the midst of turmoil of the King versus Parliament and eventual Civil Wars. Little Gidding was not exempt from all this, even to the extent of receiving Charles I after the Battle of Nasery in 1645. This attracted Eliot as he sought to grapple with the contrast of the timeless call of God to life within Him in the midst of the London Blitz. In the life lived on the stairway to Heaven, it is never and always, England and nowhere. Knowing where prayer has been valid is what makes sense over the non-sense of the bomber, ‘the dark dove in the flickering tongue’ does its worst and makes London a place of dust and ash.

Our New Testament reading reminds us that we have no hope in this world. This is not to deny the beauty and goodness to be found in the world but it is the invitation to follow Ferrar into a radical living by grace alone. TS Eliot’s Little Gidding finds our self-reliance empty as we recognise in ourselves the conscious impotence of rage as human folly.

As the bomber strikes

‘The dove descending breaks the air

With flame of incandescent terror

Of which the tongues declare

The one discharge from sin and terror.

The only hope, or else despair

Lies in the choice of pyre or pyre –

to be redeemed from fire by fire.’

Eliot is drawn to the idea of Little Gidding by his conviction that only purgation by Pentecostal fire can save. We are close to the Feast of the Pentecost now, drawn to live vividly as the Ferrars sought to do the life of the outpoured Spirit. This involved for them two daily confessions of sin in the Offices of the Church. They lived the sacrifice of praise through the day and through the night. It was not some romantic aesthetic withdrawal from the world but a bold and sober dedication to what the world really needs which is metanoia, being purged and transformed by the fire of love. The experiment only lasted twenty years, or course. The Puritans appeared to win. BUT:

‘We have taken from the defeated

What they had to leave us – a symbol:

A symbol perfected in death.

And all shall be well and

All manner of things shall be well

By the purification of the motive

In the ground of our beseeching.’

The Little Gidding community helped to fund itself and spread its message by bookbinding and small scale publishing. The community’s lasting legacy is its Gospel Harmonies, literally cutting the four gospels into strips and creating one complete narrative. There are four examples in the British Library, made for the King and for Friends. This combination of prayer and practical action was the hallmark of a community which sought to be a Gospel Harmony enfleshed. Our pilgrimage here is testimony to the genuine call to that devout life which was lived here as an example down the ages. Just before he died, Ferrar spoke about this life to his family. ‘It is the right, good old way you are in; keep in it.’ We pray, coming back again and again for the first time, as we are transformed by God’s grace, that we should keep in it ourselves.